A big concrete ball, surrounded by sea water

Subjects discussed: My novel, Brian (the novel), cinephilia, Pitchfork, Memoria

I haven’t talked much about my novel, besides noting that it exists, is going through finishing school (final edits, blurbs, cover design, marketing plan, etc.), and will be a book you can buy sometime in the early months of next year. Partly it’s because I’m still learning how: I feel very allergic to self-promotion, which is perhaps not a great sign for my future as a published author. It’s not introversion, or some inherent quietude in my character; as friends and strangers will tell you, I’m happy to not shut the fuck up about plenty of other subjects. But talking directly about my writing just feels so… unbecoming, you know. I’ve spent too much of my time in the scouring light of “online” to pretend it’s a feint at retaining some mystery, but I think it’s related to why I hate pitching: Rather than describe the work, I’d prefer to just show you the work, somewhat of a problem since it won’t be purchasable for another year.

So I’m trying. Parties will be had. Interviews will be staged. A couple of weeks ago, Jen and I attended a wedding where I met a writer friend of hers; prompted to describe the novel, Jen cut me off (“He needs to get better at this”) and delivered an astute, charming four-sentence summary that I’ve already stolen once. She also described it as “sad, funny, a little meandering, and horny,” which the writer noted are the only four literary quadrants that matter. (They’re certainly my four favorite quadrants.) What I’ll add is that one of its bigger ideas is the harrowing realization, which may arrive at any age, that you have paid attention to the wrong details of your life. That while you may be the protagonist of your own story, as they say on TikTok, you have come away with the wrong takeaways — and while acknowledging this may not upend your material existence, it unsettles your interior life something terrible.

Put another way: You ever get too stoned and suddenly feel a thousand semi-connected thoughts snap into some brutal, seemingly self-evident calculus about how fucked up everything is? But then you wonder: Is it the drugs, or is it real life? And the answer is a little bit of both? My book is about untangling that, somewhat. Also, about 9/11. It’s in the first-person; I was reading a lot of Eve Babitz when I started it, and a lot of Percival Everett when I finished it. And it’s funny, I already said that but it’s worth mentioning again.

I recently read and enjoyed Brian, a novel by the British author Jeremy Cooper, which is about a man named Kevin — just kidding, it’s Brian — who, as he approaches his 40s, becomes a member of the British Film Institute and begins to attend movie screenings every night. Many novels center around a purposefully exotic protagonist, but Brian is the type of boring person who’s everywhere in real life, and is never the subject of mainstream fiction (be it in books, movies, TV, etc.) because executives and agents say he’s not interesting enough. “He longed to be included, and dreaded it, equally,” Cooper writes, of how he’s remained on the periphery of his own life.

There’s no plot. We only stick with Brian as he watches these movies, thinks about them, and feel his inner life slowly unclench. He becomes casually friendly with some of the other BFI regulars — “the buffs,” he calls them, also older men whose lives seem to be organized around the screenings. But he remains at a distance, for the most part. Though he derives some social pleasure from participating in casual conversations about film, watching these movies in the presence of other people seems to be enough. The book is written in third-person, but Cooper follows Brian’s thoughts very closely, sometimes breaking up a paragraph into several individual sentences to demonstrate his granular, point-to-point interior monologue.

Like this.

Because Brian thinks everything through.

And you’re supposed to slow down with him.

And sit with his feelings.

Sometimes, I have to remember that the pace at which I view and process the world is different than other people’s. Consciousness is so all-encompassing that one can forget it’s fairly bespoke to your own self, and I’ve had conversations where I feel like I’ve just said something incredibly obvious only to be reminded that it’s not very obvious at all. In my early 20s I had a brief phase where I was convinced that every thought of mine fell into this “duh” zone, a belief I cured by limiting my marijuana consumption until the nighttime. So I appreciated the slow crawl of Brian’s prose, how Cooper stitches the reader into Brian’s mindset one line at a time and allows us to inhabit his inner life.

And despite being “about” a boring man, Brian’s deeper substance felt like something I hadn’t encountered so directly in a piece of art: the emotional tradeoff for becoming such an aesthetic completionist. Brian starts off by seeing one movie every day, and pushes it to two when he retires from his day job; he puts away thousands of films during his time at the BFI because he has nothing else going on. No wife, no kids, no family, no friends — just the movies, which function as a respite from the realities of the real world. It’s a solitary, lonely life, and this seems to suit him just fine. On the one hand, fuck other people, ha ha — but it’s a little sad, and it can’t help but being a little sad. Upon describing the book to my cinephile friends, they all acknowledged knowing a guy like that — acknowledged having worried about becoming a guy like that.

When I was in college, I spent three years as an aspiring cinephile, during which I saw everything in theaters, had the full three-at-a-time Netflix DVD rotation, and bought tons of books of criticism and theory by the usual suspects. This is funny today because my wife has seen far more movies than I have, but we’ll go home to Chicago for the holidays and she’ll ask me why I have several semi-marked up André Bazin readers on the shelf. There was a period where I felt like I wanted to write about movies for a living, but the truth is that I felt very lonely about this pursuit, most of the time, as I’d be sitting in my room watching On the Waterfront by myself while my friends played drinking games. Art > liver disease but sometimes you just want to be with other people, and especially in college.

Partly it was my own disposition: I couldn’t help but sound like an asshole going on about how Shōhei Imamura’s Ballad of Narayama was way better than, like, The Dark Knight, and while that’s definitely true, there’s always a time and a place. The funny thing, too, is that I didn’t hang out with other movie people because they also sounded like this and I found it unbearable. It’s embarrassing to remember, but I forgive myself by remembering many 19-year-olds are insufferable.

I thought about the demands of aesthetic devotion as the news broke of the layoffs at Pitchfork, where I worked for 2.5 years and still have (or rather, had) a lot of friends who worked there. My time there was a drop in the bucket, all things considered, and I don’t want to overstate the depth of what I observed from the inside. (Nothing worse than people stealing valor about some place they worked a decade ago.) But one broader, wildly basic thought I’ll offer is that Pitchfork was — is — a place staffed by people who tremendously care about listening to music. People who, actually, have dedicated a good chunk of their time to non-cynically thinking about new and old records.

A lazy line of critique was that the site pivoted too severely to “poptimism,” but the people making those critiques don’t listen to a fraction as much music as the Pitchfork staffers did. And I don’t say this as proof of how amazing they were, or how they should’ve kept their jobs, or how Addison Rae is actually good — I just mean that there was a very earnest, devoted level of commitment to engaging with music that’s impossible to fake unless you’re built for it. This was what the staffers shared with the musicians they covered: not the ability to make music (though some Pitchfork staffers played in bands), but the desire to be surrounded by music all of the time.

The infuriating thing about the Pitchfork layoffs is that you got the sense, reading the reporting and hearing how the news was communicated, that nobody in charge ever quite grasped the site. There was a sincerity that just didn’t translate, because passionate devotion is not something that the people in control of media layoffs understand very well. Listening to records is not something that’s easy to monetize. It doesn’t really serve an obvious social function, other than allowing you to connect with other people who listen to records. There’s no other publication at the level of Pitchfork’s visibility that would run a long review of an album like, say, Salamanda’s In Parallel. You can maybe quibble about the exact value that review provides — but you can’t argue that anything is improved by removing it from the ecosystem. Yet they couldn’t sell luxury watch ads against that, and so they decided to nuke the site’s institutional memory and editorial structure. It’s a war on paying attention, it really is.

Last week, we saw Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria, a movie that was released in 2021 but is only ever playing in theaters, with no streaming options. The movie is about an anthropologist named Jessica (played by Tilda Swinton) who, one day, begins to hear a blunt and unsettling noise in the background of her everyday life: “It’s like a big concrete ball… that falls into a metal well… and is surrounded by sea-water,” she describes to an audio engineer. Jessica starts to hear it all the time, when she’s at dinner with her sister or walking through the city. Sometimes, you look at her distracted face and wonder if she’s hearing the sound even though it’s not audible for the viewer. She worries she’s going crazy, and embarks on a long journey to figure out just what exactly is happening, to mixed results.

Even if it were streaming at home, the movie basically has to be seen in theaters — the sound is designed to fill up that big, cavernous room, and you’re meant to share Jessica’s dread and anticipation as this leaden thump suddenly hits from nowhere. Eventually, it becomes clear that the sound has some practical origins, but I think it’s also a metaphor for culture itself — the way that we’re all just walking over and surrounded by thousands of years of people, places, and things, all stacked and melted into indistinguishable history, but sometimes there’s a rumble from the depth that dislodges a fragment of all this, and plants it in your brain.

Thump, thump, thump. Every time you hear it, something’s different. Jessica continues to pay attention, and her obsession eventually flips. Slowly, she seems to accept that she might be a vehicle for this inexplicable phenomenon, even as the people around her think she’s losing her mind. As the movie goes on, Tilda plays it like she’s almost looking forward to this sound that once beguiled her. And you listen with her, growing used to the sound, wondering if there’s something to be gleaned from it but allowing that maybe it can only bowl you over.

Professionally speaking

I talked to the architects of the Barbie soundtrack, which should be understood not just as a creative accomplishment but as a feat of high-level administrative competence, for the New York Times.

I wrote a bit about the new season of True Detective for The Atlantic. It’s not bad, but anyone who says “it’s the best since season 1” is smoking crack.

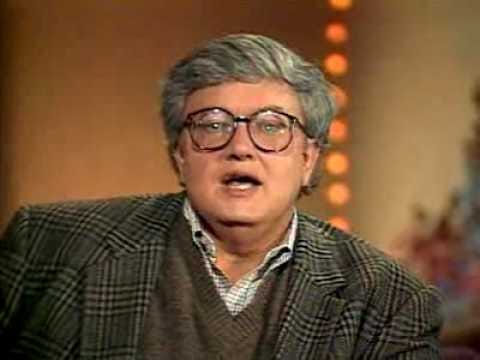

The Siskel & Ebert clip makes me sad those guys never got to see The Irishman or Killers of the Flower Moon